MKG127, Tkaronto/Toronto

November 22 - December 20, 2025

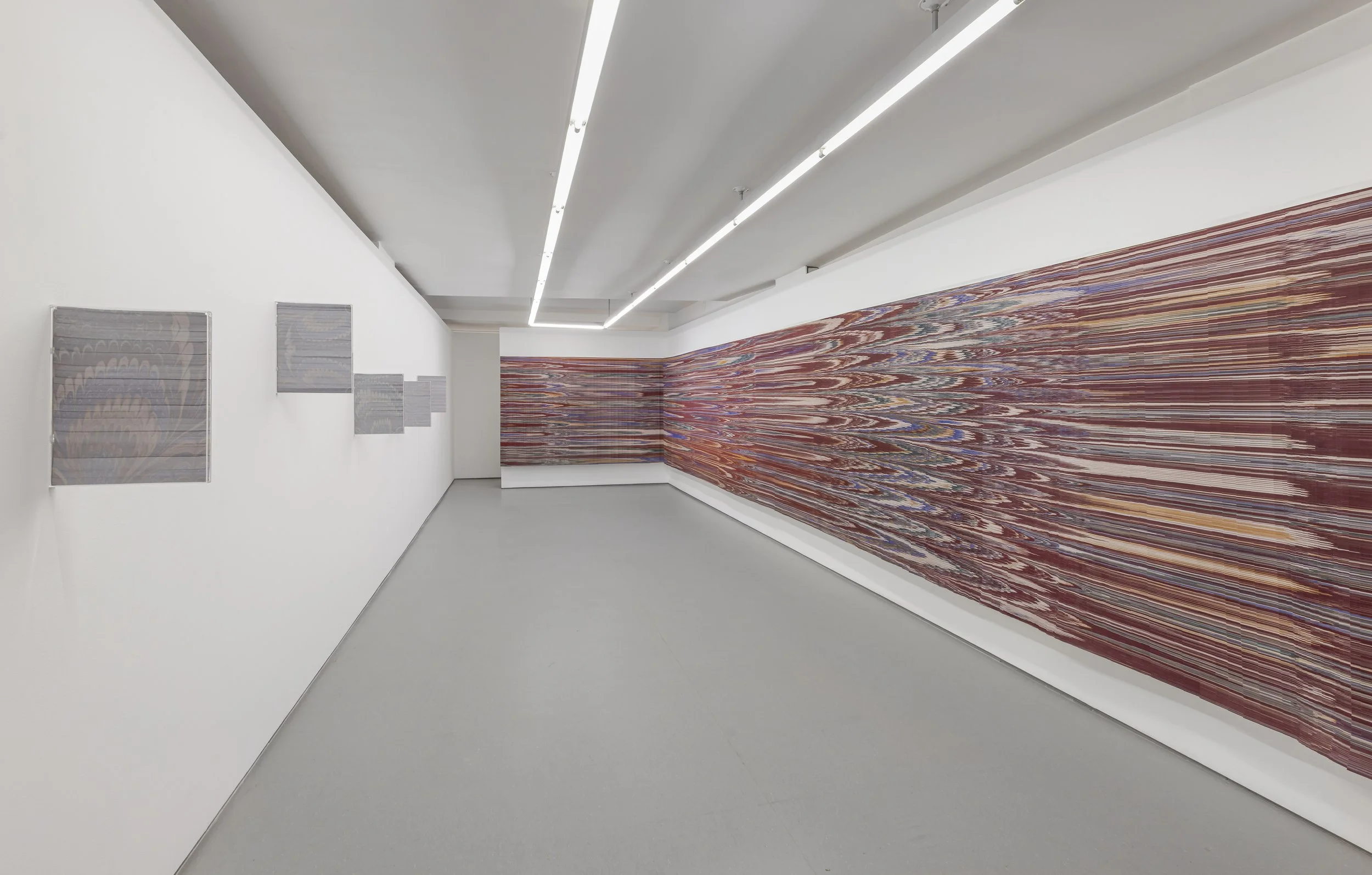

Photos: Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy MKG127

The exhibition Dust Jacket emanates from a nineteenth century marbled pattern: the kind of pattern that proliferated as endpapers in Victorian books. Such papers present floriated swirls in rich jewel-tone hues that echo the veining in stone or the patterning of feathers and shells. The scalloped designs were formed by looping and twirling a stylus through pigments scattered atop a thickened water bath—a floating iridescence akin to a marine oil spill. The flickering effect also recalls something of the shifting brilliance of nacre or mother-of-pearl, the strong, glimmering material that lines the inside of the shells of some sea creatures. In presenting a baroque effusion of surface that creates thousands of tiny fissures in its archival reference material, Dust Jacket engages the intimacies of water, petroleum, and shell held by nineteenth century European marbled papers.

The same nineteenth century marbled pattern appears across the exhibition’s three main bodies of work. The pattern visually references shells, florid shell-bouquets, or countless other Victorian crafts created from shells. Victorian shellwork, or the practice of encrusting objects with shells, made use of shells collected from the seaside meticulously applied in highly contrived designs that, like marbled papers, result in ornate, controlled instantiations of nature. As such, marbled papers and the shellworked craft invite us into strange nineteenth century interiorities—whether the hollow of the shell itself, or a grotto unfathomably swathed in thousands of shells, or the domestic interior of the Victorian manor home where shellwork was practiced.

The nineteenth century shell also leads us to the interior of a ship, a vessel that would come to transform the shape of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In 1892, the heirs of Marcus Samuel’s small seashell shop in London which sold tropical seashells imported from Asia, including “small shells for ladies’ work,” built and successfully sailed the first oil tanker capable of carrying vast quantities of oil through the Suez Canal. The tanker was named The Murex after a large, gorgeous, spiked shell, and the company was called The Shell Transport and Trading Company, today, the Shell oil and gas company, reflecting its origins in the shell curio shop. More than just a reflection of its beginnings, it was the Samuel family’s access to, and knowledge of, colonial trade routes established through the trade of seashells that led them to oil and the global transportation of it.

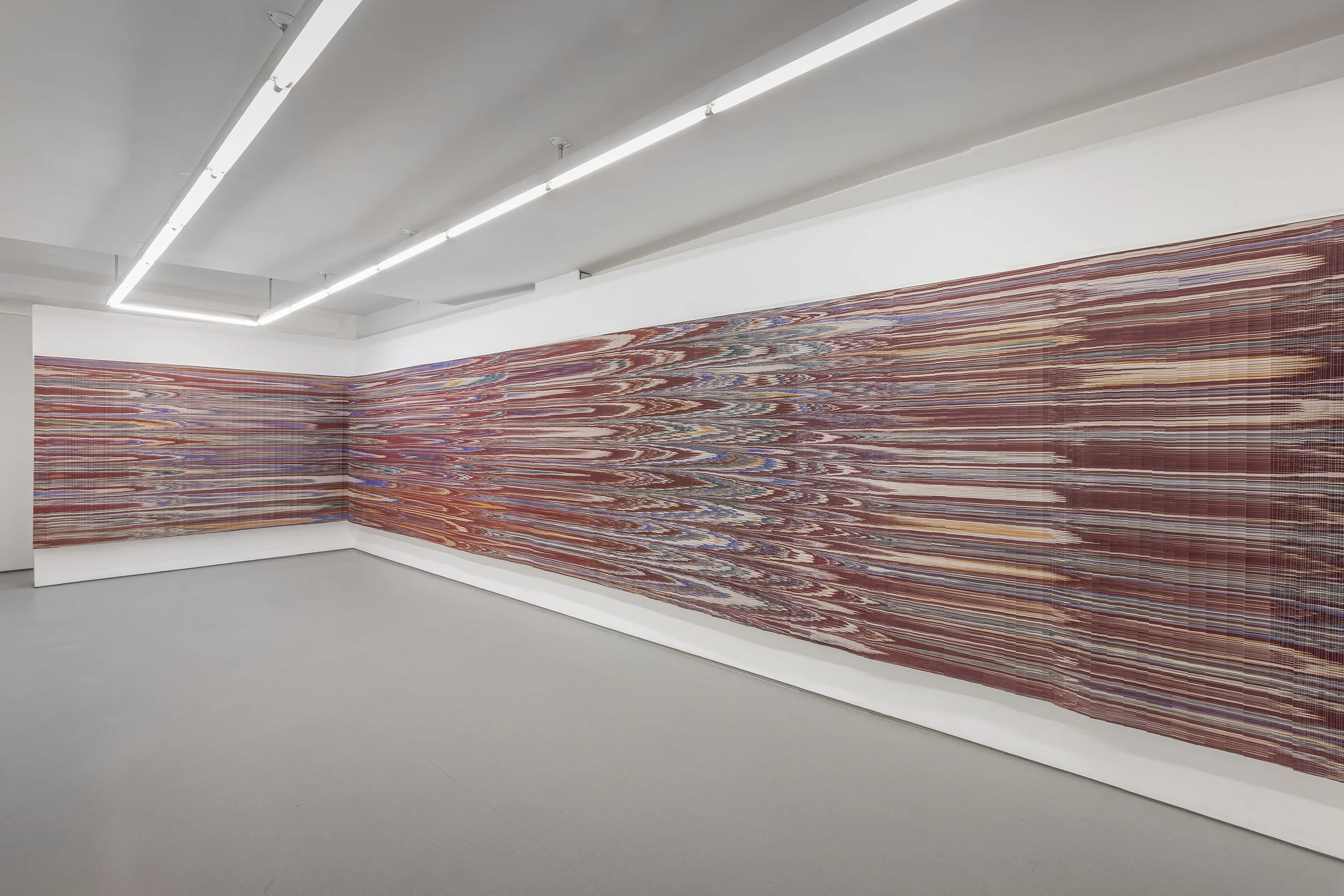

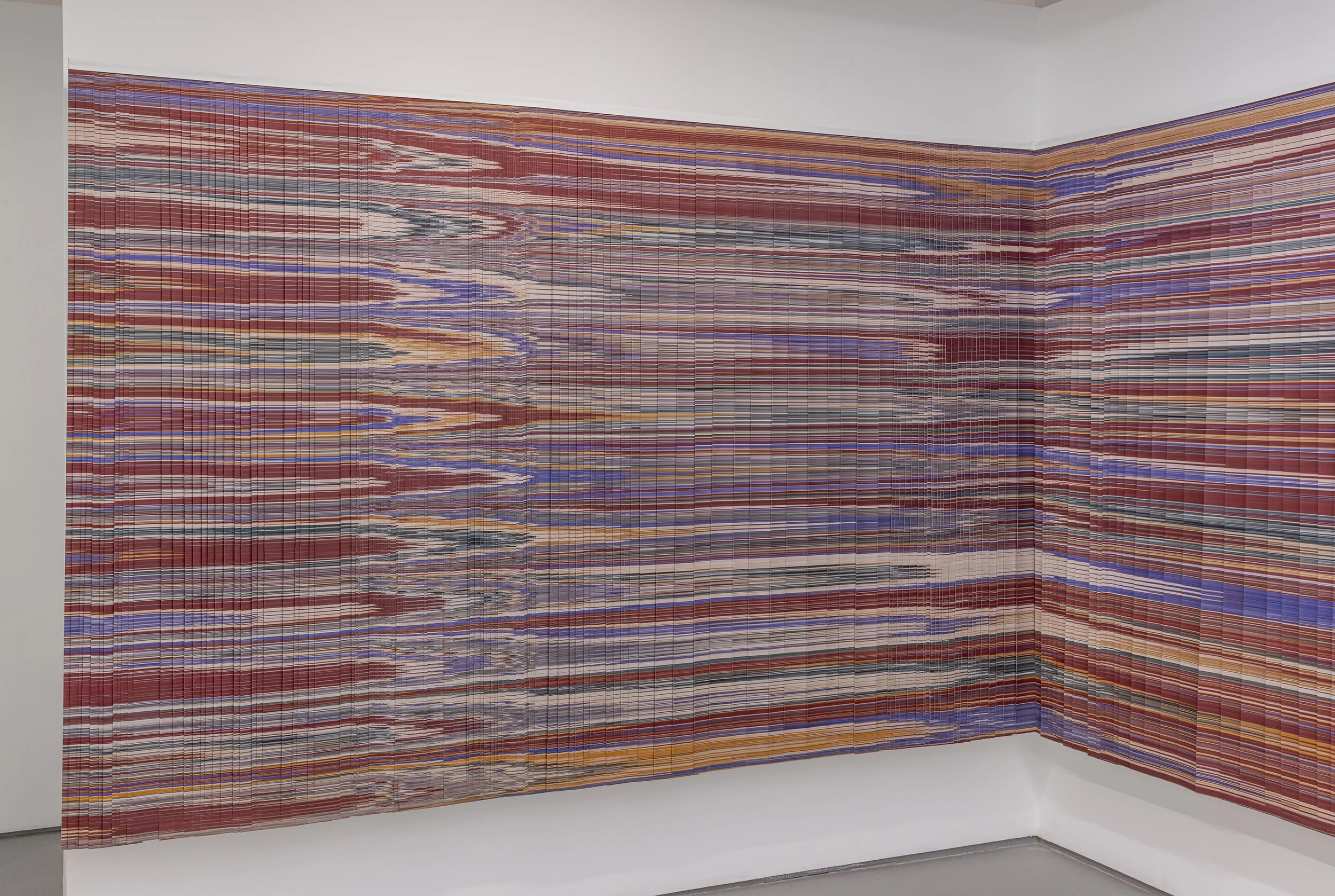

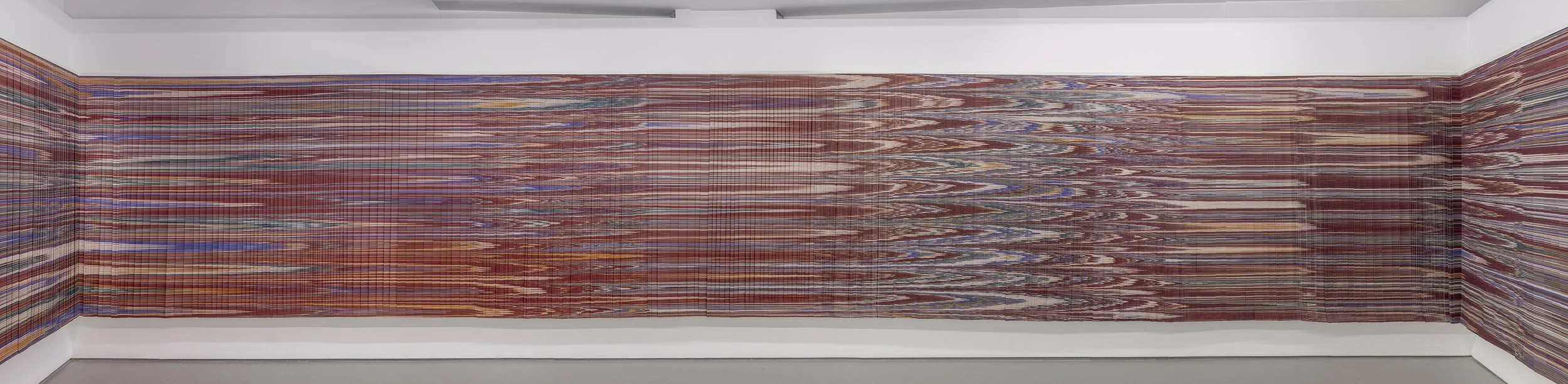

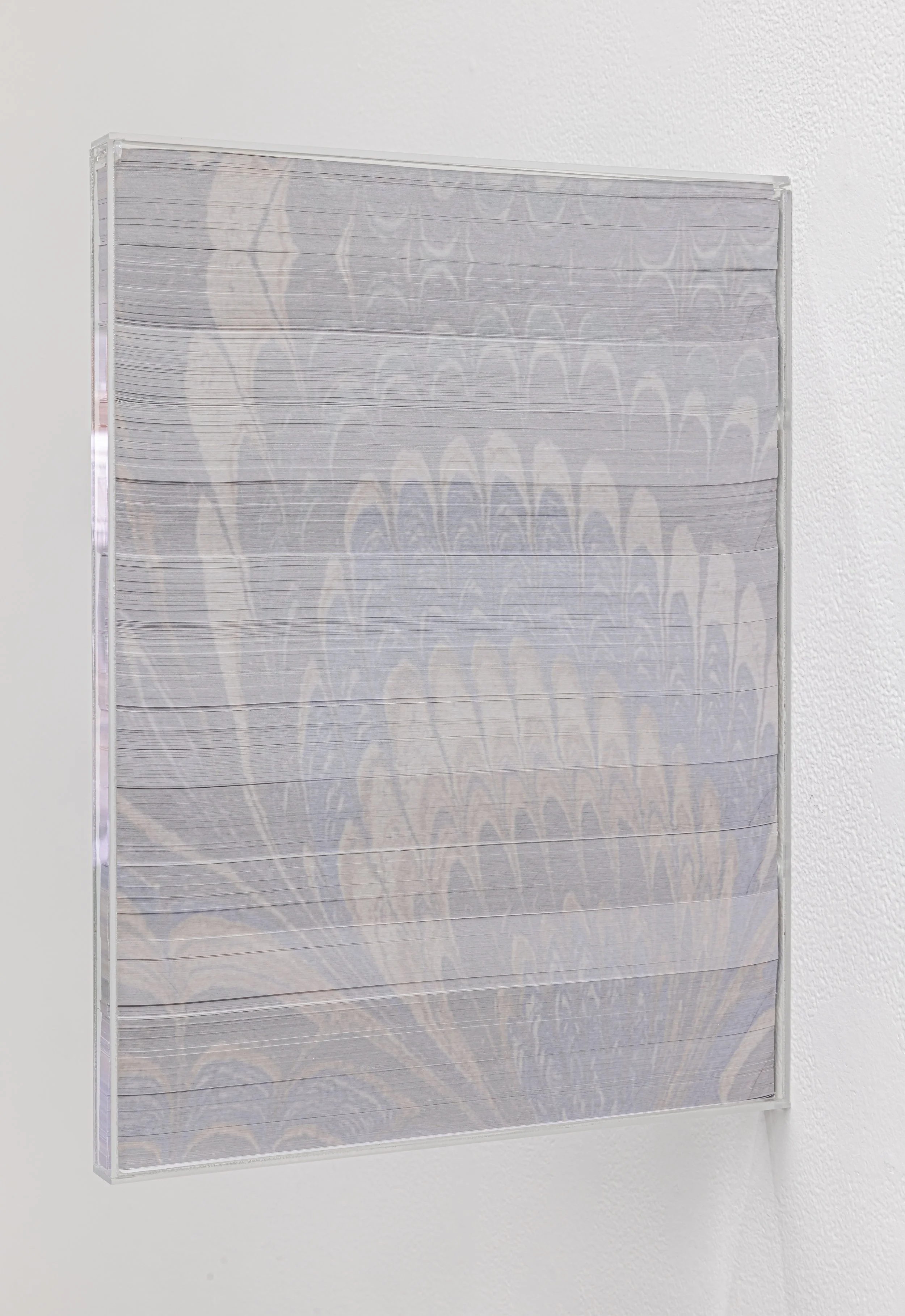

The exhibition’s eponymous sculptural installation, Dust Jacket, consists of over one-thousand two-hundred unique digital prints, produced on long, tall slivers of bond paper. Each print features an intricate set of parallel lines that run horizontally across its slight width in various weights and colours that gradually shift from one print to the next. The scale of each print echoes that of a vertical blind slat, and indeed, the prints are hung in an orientation that evokes a set of vertical blinds. Here, the blinds proliferate excessively, building density and bunching into a luxurious fan of colour before thinning out again. In the denser areas, there are moments where the original marbling pattern becomes discernible or legible. Yet, this steadfastly remains a distributed legibility, where the image or pattern is proliferated across dozens or hundreds of prints. Where the prints are sparser, the overall marbling pattern begins to fall apart, and one attends solely to the rich patterns of lines. Curiously, the shell motif from the original marbling print is stretched and altered into a flickering technicolour chemical flame, perhaps, or a peculiar sound wave extended across the installation’s excess of surfaces. Here, the wateriness of the marbling pattern is reactivated. The pattern seems to glint, reflect, mirror and slide. Formed from what once appeared as the striations and scalloped edges of a shell bouquet pattern, the stretched parabolic lines might also recall the foamy, v-like trail of disturbed water that flows behind a vessel as it moves through a body of water, echoing the very process of marbling itself, where floating colours are pushed and combed through a water bed. The resulting pattern is an elaborate wake-choreography, evidencing the traces of so many trails of disturbed water. It is almost as if Dust Jacket, in moving through this nineteenth century marbled pattern one paper-thin cross section at a time, has surfaced the afterimage of the vessel in the elongated wake of the marbled pattern’s striations.